Alternate Reality

Defying the nation’s rightward turn, Antioch’s Coretta Scott King Center hosts a conference to inspire and strengthen all manner of progressive activism.

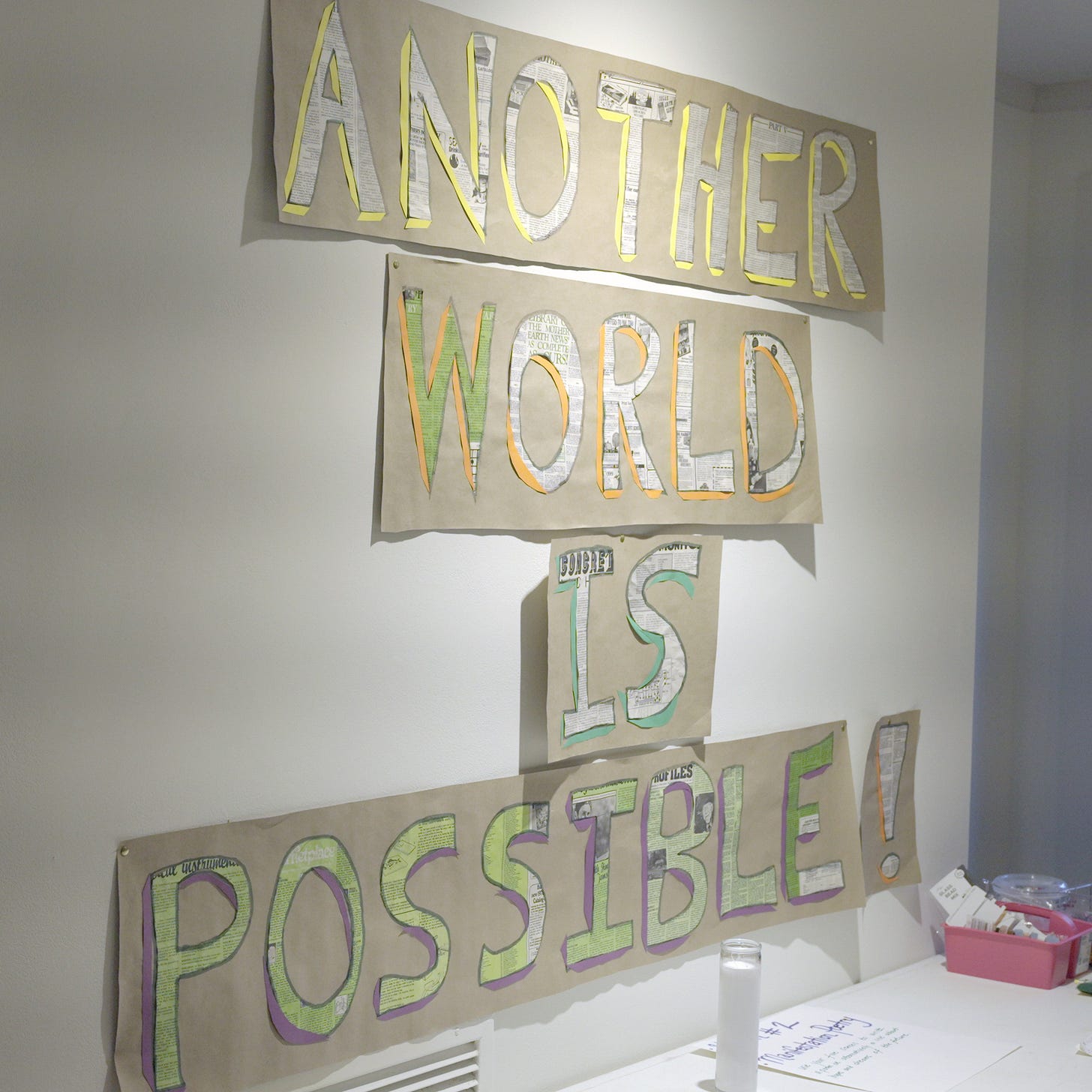

On a day in mid-February when the Ohio Senate voted to ban diversity, equity, and inclusion activity at all public colleges and universities in the state, Antioch opened a 3½-day conference with DEI values at its core. Organized by the Coretta Scott King Center under the title “Another World is Possible: A Global Racial and Social Justice Summit,” it brought together scholars, visual and performing artists, activists, and community organizers to imagine a progressive future vastly different from the polarization, ethnic and racial tension, and intolerance exemplified by the anti-DEI, anti-trans, and anti-immigrant policies spreading from the White House through federal agencies and around the country. Recalling the 1951 Antioch graduate for whom the center is named, President Jane Fernandes said the summit was a call to action and collective resistance.

If its purpose was serious, the conference was anything but downbeat, offering a mix of social and educational strategy, art, and performance. From the start, convenor Queen Meccasia Zabriskie, the CSK Center’s director, put the 84 attendees in a convivial mood. They were there, she said, “to fortify ourselves and build out important networks of support.” A student of West African dance, she infused the program with movement, explaining, “We have to bring the body in when we talk about liberation.” Picking up a pair of drumsticks on the first evening and knocked them together in time with a Ghanaian number, “Akwaaba” (“Welcome”) performed by BabaaRitah Clark and her Columbus-based All Women’s Drum Group. Zabriskie went on to introduce the Un/Commoning Pedagogies Collective, a group dedicated to radical anti-racist approaches to teaching and learning, who at several junctures led the whole conference in exercise, meditation, and reflection.

Miles Iton captured the Summit’s spirit. A former student of Zabriskie’s at New College who studied in Taiwan as a Fulbright Fellow, he founded Lo-Fi Learning, which teaches English as a foreign language through hip-hop. On the first evening, he paired with public school teacher and community organizer Truth Garrett in a dialogue on the music genre, which emerged from blighted urban neighborhoods and, over a half-century, influenced the world. Their conversation ranged from the cultural relevance of Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Superbowl half-time show (“No weak verses”) to tennis great Serena Williams’s “Crip walk” at Wimbledon, hip hop’s value in teaching such English rules as the use of similes, and how the music industry treats artists. A segue to Kanye West sparked one of the liveliest audience exchanges of the summit, and introduced the portmanteau “shitstem,” generally meaning oppressive forces, to approving laughter. Iton and Garrett finished with a song. Later in the summit, Iton participated in a panel discussion of his 2018 documentary, Sincerely, the Black Kids, an account of the challenges faced by Black student leaders, and a panel entitled “Student Organizing for Changes.” He also spoke with fifth and sixth graders at a local school.

The conference drew active participants from a number of colleges, mostly in panel discussions and workshops. Notable formal presentations included “Lessons for Today from the Reconstruction Era of the 1870s,” by Kevin McGruder, associate professor of history Antioch. He compared the current “period of racial retrenchment” with previous episodes in “the long history of cyclical backlash” by Whites against perceived threats to their own progress—notably, the hostile reaction to Reconstruction (1865-76). A specialist in real estate, McGruder made a case for present-day activists to make Black wealth accumulation a priority and adopt, as a tool, increasing home ownership. “If that tactic is combined with strategies of direct action, a sustained movement can be created that can achieve measurable successes,” he argued in a PowerPoint. A precedent can be found in the formation of all-Black towns in Kansas and Oklahoma by formerly enslaved people from Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Currently, 41 percent of Black households own their homes, as opposed to 71 percent of Whites. This disparity helps to account for the enormous wealth gap between Blacks and Whites, since home-value appreciation is a principal means of acquiring wealth in the United States.

One example of “racial retrenchment” is the conservative backlash against diversity efforts in education, from the Supreme Court’s rejection of affirmative action in university admissions, the recent U.S. Department of Education’s sweeping threats to cut off funding to institutions that that considers race in any aspect of campus life, and the Ohio Senate’s ban on DEI activity to book bans and dilution of history to remove so-called divisive content. Among those bucking this trend is Nicholas Payton, assistant professor of human services at Simpson College in Indiana, who shared research on anti-racist teaching approaches that empower students of color. He offered recommendations for creating emotionally safe spaces, identifying systemic barriers, engaging students collaboratively, developing anti-oppressive curricula, and implementing a shared operational classroom model.

Ohio Wesleyan University’s summer bridge program for historically excluded students—including first-generation, students of color, and queer students—takes a wraparound approach, with lots of mentoring in areas ranging from public speaking to personal hygiene. As explained by Jason Timpson, director of multicultural student affairs, and several colleagues, the cost-free program encourages families to become partners, and includes supervised trips to destinations that exemplify such tough social issues such as environmental racism (Flint, Mich.) and the history of slavery (graves of enslaved people in Richmond, Va.). Cohorts that completed the program have outpaced OWU’S overall retention rate. The program has been embedded in the admissions process, and the school is looking to adapt the model for third-year students.

Ever since Socrates engaged students in his signature dialogues, academe has prided itself on rational discourse. But the war in Gaza has so inflamed campuses as to render a calm exchange on the subject almost impossible. That hasn’t stopped Awad Halabi and Elliot Ratzman, who have been discussing the conflict before Ohio audiences since it broke out in October, 2023. Halabi, a Palestinian-American professor of history at Wright State University, spells out why he contends Israel has committed genocide, sticking to well-documented evidence. He cites, among other things, respected groups and individuals such as Human Rights Watch’s executive director; the International Human Rights Clinic at Boston University’s School of Law; Omar Bartov, an Israeli-born professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Brown; and Doctors Without Borders. Ratzman, a Fellow of the Raoul Wallenberg Institute at the University of Michigan, who is Jewish, agrees with Halabi, and says peace activists need to think through “how we might move forward to prevent whatever U.S. policy exacerbates evil,” and work to “bring in the Jewish community as partners.”

The trans community finds itself a particular target of anti-DEI campaigns. “The way we’re being used as a wedge issue is being increased exponentially,” Shelby Chestnut, executive director or the Transgender Law Center, said at a panel discussion titled, “Advocating for Transgender Rights.” Chestnut pointed out that no fewer than eight of President Trump’s executive orders “limit the health and livelihood of trans people,” and said poor people in the community face the loss of certain public benefits. One order by President Trump declares, “It is the policy of the United States to recognize two sexes, male and female,” and says his administration “will enforce all sex-protective laws to promote this reality.” Many Americans recognize that discrimination against trans people exists, and a majority support laws to protect them from bias in employment, housing, and public spaces. But Chestnut, president of Antioch’s Board of Trustees, said when it comes to competitive sports and restrooms, people don’t want to talk about it. In seeking to win public support, panelist Diana Boggs, stressed the importance of working at the local level: “Sometimes you are your own activism just by walking around.”

While the Christian Right plays a powerful role in contemporary U.S. politics, the CSK Center and the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. serve as reminders of the influence of religion in movements for social justice. During a discussion on Black Liberation Theology, panelist Seth Pickens, a former pastor of Zion Hill Baptist Church in Los Angeles who is now managing director of the Homelessness Policy Research Institute (HPRI) at the University of Southern California, urged attendees to remember James Cone (1936-2018), whom he called“one of the greatest liberation theologians.” Cone, a professor at Union Theological Seminary, where Pickens studied, was the author of A Black Theology of Liberation (1970). He later recounted that he wrote the book after “it had become very clear to me that the gospel was identical with the liberation of the poor from oppression.” In a post-conference email, Pickens cited “severe declines in (church) attendance and giving over the last 50 years,” adding, “I challenged us (panelists) to imagine what might be next, instead of just inviting people to participate in something that is apparently passe.” The panel, subtitled “Building Community, Building Resistance, Building Power,” also included multidisciplinary artist Kaci M. Fannin, founding producer of Banjigirl Productions; Betty Holley, professor and academic dean at Payne Theological Seminary; and the Rev. William Randolph, pastor of the First Baptist Church of Yellow Springs.

Timely topics at other panels and workshops included grass-roots organizing for human rights in Dayton, resisting authoritarianism, “Creating Safer Spaces for Trans People of Color”; “Navigating DEI Challenges with Anti Fragility”; “Raising Culturally Competent Children in a Culture-Conscious World”; “Multimedia Performance Artwork” by the Bridge Club Collaborative: and “Intersecting Abolition: A Call for Nuclear and Prison Abolition.” This last included Mary Evans, ’20, and Aaron Nell, from the Higher Education in Prison program at Wilmington College, and Tanya Maus, of the college’s Peace Resource Center. Wilmington College last year won approval to renew bachelor’s-level programs at three Ohio correctional institutions. Evans has produced a WYSO radio-web-podcast series called Re-Entry Stories, featuring conversations between people who were incarcerated.

The summit departed from the typical academic-conference format with its attention to art—from giant murals and a continuous exhibit of paintings in the Herndon Gallery to multiple sessions devoted to film and video. A showstopper, Mareas/Tides, riveted a large and enthusiastic crowd at the Foundry Theater. Created and performed by dancers and musicians on the faculty of Denison University, it presents the world of the African diaspora, colonization, and native island peoples through dance, video, artifacts, song, and an improvised score based on jazz, blues, folk melodies, Gospel, and Latin salsa. A video of surf breaking on the shore beneath a giant moon fills a screen that takes up the width of the stage. Playing throughout the piece, the video makes the ocean, which once carried ships crammed with captive Africans and now surrounds and helps sustain islanders, a central player. The performance’s authenticity adds to its power. Dancer-choreographer Ojeya Cruz Banks “is inspired by her heritage as an African American and Pacific Islander from Guam/Guåhan,” the program notes state. Her colleague and creative partner, Marion Ramirez, is a Puerto Rican dance artist whose work draws on her Caribbean background and experience performing in Puerto Rico, Cuba, Europe, South Korea, and the United States.